A few months ago, we had a funeral for a bird. It was beautiful and last minute as these things always are, and I’ll get to the details momentarily.

For the story actually begins a few years ago.

I had just finished my first year of seminary and was enrolled in a CPE program (clinical pastoral education), where I spent my days running around a giant hospital learning how to be a chaplain.*

I had recently endured my fifth miscarriage in two years, and I felt like I had been set adrift on a sea with no compass, no anchor, and no shipmates. My spouse and I had decided to stop trying for a baby for a while and reassess what was next for us.

I was adrift in many other ways during that season. Grief had come spilling out of a well-constructed dam of fundamentalist faith, and I didn’t have a spiritual home in which to rest and be nurtured.

I had enrolled in seminary after years of teaching because I sensed a seismic shift in vocation, but I wasn’t sure what the landscape would look like once everything settled down. Taking the advice of my academic advisor, I tried a lot of things, including CPE.

I went into the summer intensive ready to think about something other than the cemetery my uterus had become.

And then one day I realized I had not gotten my period in some time and went looking for the pack of pregnancy tests I had hurled into my closet after my last miscarriage.

The test was positive.

That didn’t mean much to me at that point considering I had seen a positive test five times before that and those had met a bloody end.

But still, I was angry and confused.

I was frustrated that my summer of spiritual intention had been upended by a story I had grown weary of. I mostly tried to ignore what that test had said was happening.

And then one day, I came home to a flutter of wings above our front door and realized that a pair of swallows had been building a nest while I had been keeping my head down. I came home the next day to a mama bird sitting dutifully in the nest, giving me a wary eye.

Over the next few weeks, I checked on the nest when I left and when I returned. I watched the fuzzy heads pop up, chirping angrily for breakfast. I whispered encouragements to the proud parents. I shielded my head as they reminded me to steer clear of their babies.

One night, when we had company over for dinner, I warned the guests to duck as they were exiting the house because the birds’ nest was right above our front door frame, and they had already settled in for the night. When our dinner guests opened the door to leave, one of the birds swooped into our living room, reminding us of the boundaries we must abide if we were to coexist on each other’s property.

I had come to see this little nest as a sign of hope for my own pregnancy. I tried to hold that hope lightly, but it’s hard when you hear the bird song in the morning and see the fuzzy heads poking out of the twigs when you get home each day.

A little while later, before the baby birds had begun flying lessons, our roof was damaged in a storm and soon after, repairmen came to replace the roof. They mentioned off-handedly that they would knock the birds’ nest down for us if we wanted.

My spouse told them sternly that they would do no such thing.

But a few days later, I came home to an empty door frame. The nest was gone. The birds, too. Their home had been destroyed, and the parents had fled.

I had read that swallows may return. They didn’t. I don’t blame them.

But the pregnancy from that summer held on and eventually became my daughter.

Years passed.

I finished seminary.

I became a pastor at a church.

We moved houses.

I got pregnant again, this time with my son.

I left the church and became a pediatric chaplain.

Then one day, as I was walking out my front door, I heard a flutter of commotion above my head and looked up.

And there was a nest, an engineering miracle of mud that would hold multiple birds at one time.

And from that nest, the mama bird peered down at me.

I quickly left the porch but held on to my wonder.

Over the course of the next few weeks, the Dargai Household Happiness Meter was directly linked to the growing baby birds. We watched as their tight-lipped beaks peered over the nest during the warm summer afternoons. We stepped over the accumulating pile of bird excrement on our porch. We counted the little fuzzy heads each morning: 1, 2, 3, and yes, a 4th baby bird!

Like a fool, I encouraged my daughter to name the birds. “Name all four of them,” I coaxed her, allowing joy to swallow up any kind of biological sensibility.

She named them nonsensical names kids come up with: Pumpkin, Lantern, Pizza, and Pinky. I wondered when we would see them fly as I dropped her off at school and drove to work.

And then I received a call one afternoon from my mom, who had picked the kids up early and taken them to our house.

“There’s a dead baby bird on your porch. Annie was the one who found it,” my mom told me.

My heart sunk. It had been a heavy day at work, but I knew that we had to do something when I got home. I mean, what is the point of having a pastor for a mom if you can’t throw together last-minute funerals for animals?

“Okay, don’t move it. We’ll put on a funeral when I get home,” I instructed my mom, who already thought my vocational choice is odd.

I ran upstairs to the NICU chaplain, who I knew had just presided over a fish funeral with her kids and asked her to help me with the liturgy. She wrote a prayer for the funeral and texted it to me as I drove home and brainstormed what to bury the bird in and how to field questions of death that my six-year-old always has at the ready.

When I pulled up to the house, I could see the bird laying on the porch.

My job necessarily entails encounters with the death of children. It is hard and fraught and a piece of the work that I don’t talk about at most dinners, but it is a reality that is present with me. On some days, it makes me cynical. And on other days, it makes me hyperconscious of how frail our tethers to life are.

So on that day, the tiny, fragile body of a baby bird on the porch brought me to tears. I cried over my steering wheel before mustering the willpower to walk into the house.

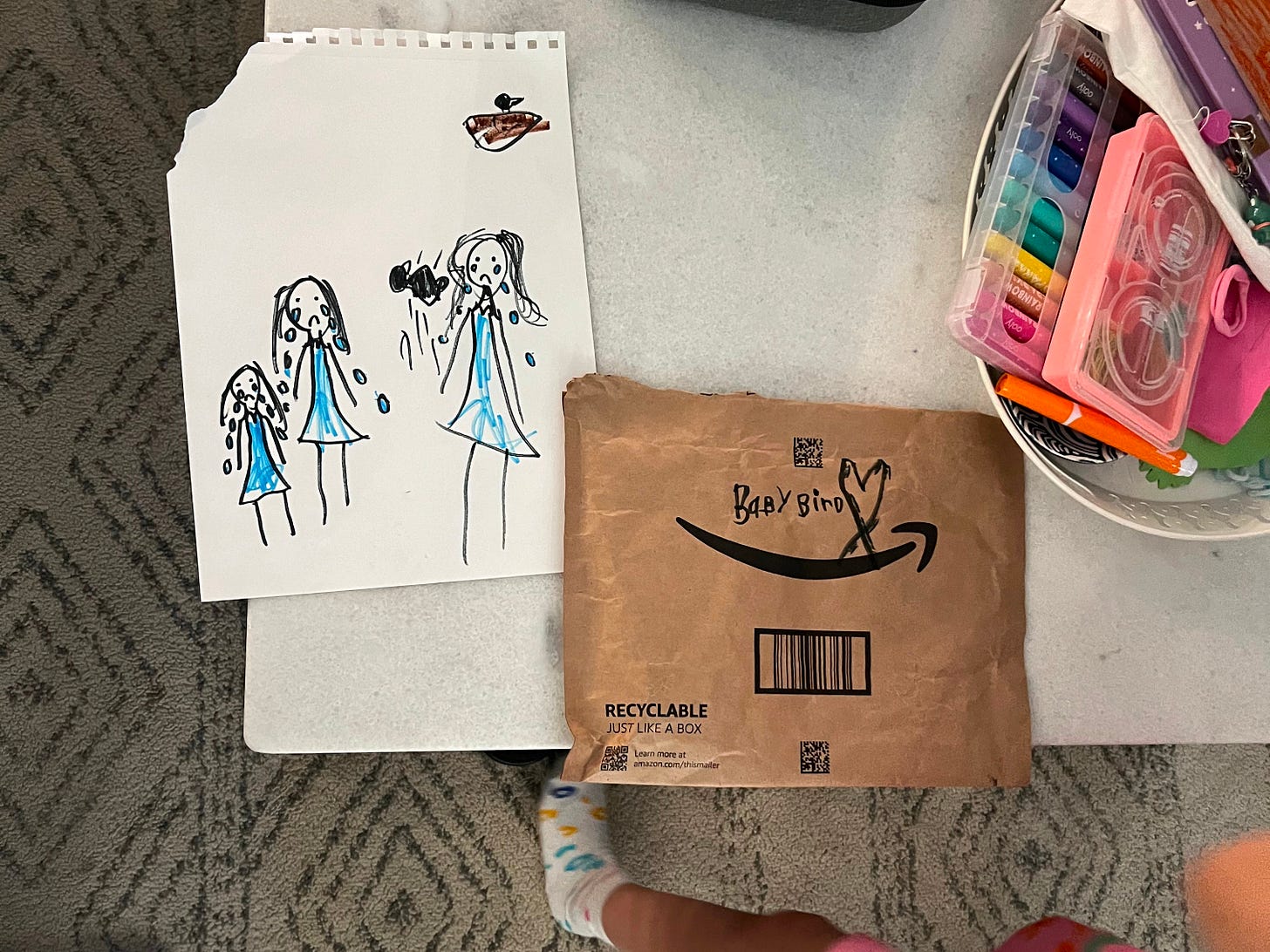

My daughter greeted me with her play-by-play of finding the bird and a picture she had drawn of what happened.

I scrounged up a brown envelope from Amazon and had her write on it. We inserted her beautiful portrait that showed not only what had happened to the bird, but also how it affected all of us. And then I put on gloves and picked up the bird’s body and sealed it in the envelope.

We went out to the garden–me, Annie, my husband, and my mom, who held my son–and dug a hole.

I read the prayer my friend, Britt Luby, had written:

Creator God,

For weeks we have looked out our window at the threshold

And welcomed this family of birds into our family.

With gentle voices, we greeted them

And we loved them.

God, today the unthinkable has happened,

The body of this baby bird has broken,

And our hearts feel broken, too.

God, we pray for this little bird,

We pray that she is safe and loved and with you.

And we pray for her parents, Bandit and Chili,

and her brothers and sisters who miss her.

Please make sure they know, God,

How treasured they all are. By us and by you.

We are sad, God,

And it is okay to be sad.

The life of this little baby bird was short,

But the beauty of her existence remains.

The world is better because this bird was in it,

And we are better because we knew her.

May we hold onto the memory of this little bird with tenderness,

Knowing that the God who made her

Is with her still.

I asked Annie if she would like to say a few words about the bird. She did.

She said, “I liked having the bird. I liked the way she sang to me. I’m sad she died. I will miss her. I love you, Pinky.”

And then I played “Like a Bird” by Nelly Furtado on my phone, and we lowered the bird into the ground. Annie found a rock and put it on top of the dirt where we buried the bird.

For the entirety of the funeral, the mom and dad, whom we had dubbed Chili and Bandit after the beloved parents of Bluey, perched on the gutters of our house and stood guard.

After we put the kids down for the night, I thought about the other nest, the one from the summer when I was pregnant with my daughter.

I thought about how the parents must have returned to find their nest gone and their baby birds no more.

How they did not even have their bodies on the pavement to tend to.

I thought about how distraught they must have been.

I thought about them moving on to another place after that heartbreak.

I thought about what it felt like to start over.

I thought about how much I was anthropomorphizing these birds.

I thought about how I was thinking about myself, really.

—-----------------------------------------------------------------------

*I’m still learning, for what it’s worth.

Thank you, Ashley. Grateful for you!